- Home

- Helen Forrester

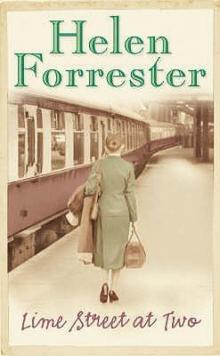

Lime Street at Two

Lime Street at Two Read online

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

The generals, the institution can select a strategy, lay it all out, but what happens on the battlefield is quite different.

Count Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoi 1828-1910

To my husband

1

THE huge clock still hangs in Lime Street station, Liverpool, and marks a convenient spot for travellers to be met. During World War II, almost every girl in Liverpool must have written to a serviceman coming home on leave. "I'll meet you under the clock at Lime Street." There were always women there, dressed in their shabby best, hair long, curled and glossy, pacing nervously under that indifferent timepiece. Every time a train chugged in, they would glance anxiously at the ticket collectors' wickets, while round them swirled other civilians, and hordes of men and women in uniform, khaki, Navy blue, or Air Force blue, staggering under enormous packs and kitbags. Some men wore foreign uniforms, with shoulder flashes of refugee armies, navies and air forces. No matter who they were, they all shared the same expression of deep fatigue. This huge vortex of uprooted humanity was supervised by stolid-looking military police standing like rocks against a tide. Some of them were American Snowdrops, so nicknamed because of their white helmets. Occasionally a single English civilian policeman stood out amongst all the other uniforms, a reminder of peacetime and sanity, when a quiet, "Now move along there, please," was enough to reduce a pushing crowd to order.

The station may be rebuilt, the generations pass, but the ghosts are still there, ghosts of lovers, husbands, sons, withered like flowers on distant battlefields long forgotten, and of mothers, wives and sweethearts long since dead. Amongst those kindly shades stands Harry O'Dwyer, the fiance of my youth, a ship's engineer, lost at sea in 1940.

I do not know how I got through that dreadful summer of 1940, after the news of Harry's death, or the long, hopeless year of 1941. It was a period when the Merchant Navy was decimated by German submarines and aircraft. Once a man was at sea, there was not a moment when he was not in acute danger. Over the bar, in Liverpool Bay, the U-boats waited, likecats at a mousehole, for the slow, ill-defended freighters entering and leaving the ports of Liverpool and Birkenhead. If they survived the submarines, they could strike acoustic mines, magnetic mines and other menaces plopping about in the heaving waters.

Even snugly moored in dock, ships were often the target in air raids; and the homes of their crews, packed in the dockside areas, were frequently destroyed.

I lived within a mile of the south docks, with my father and mother, four brothers and two sisters. I was the eldest child. We were a most unhappy family, our lives fraught with the bitter quarrels of our parents, and our considerable penury.

When I was a child we had lived in comfortable circumstances, but in 1930, my father had gone bankrupt, as a result of the Depression. In an effort to find employment. Father had brought us to Liverpool, his birthplace. Like most of the people living in the south of England, he had no notion of the horrifying effect of the Depression in the north. The unemployment rate was 33 per cent and there was almost no hope of work. We had sunkinto an abyss of poverty, which I have described in earUer books.* By 1940, however, we had begun to climb out of the pit into which we had fallen, though we were still very poor.

My parents were still filled with the Public School snobbery of their youth, so I had told them nothing of my engagement to Harry O'Dwyer. They would have immediately condemned such a union as beneath me. Harry was from a respectable Irish working-class family and a Roman Catholic, originally intended by his family to be a priest. Since I was a Protestant, we had agreed to be married quietly in a Registry Office soon after I was twenty-one, when I would not need my parents' consent. Harry had bought a little house, which was not quite complete when he was killed. I was twenty-one years and two months old when his mother told me of his death, under the very odd circumstances that she did not know she was talking to her son's fiancee.

In 1940, I was a neophite social worker in Bootle, a small town sharing a common boundary with Liverpool. It was a Roman Catholic area tightly packed with overcrowded terrace houses, factories and timber yards, hedged in by the docks along the river. Though the poverty was very great, Harry was proud to say that he was a Bootle man; men had sailed from Bootle since the Anghans settled there in AD 613, and perhaps even before that.

One morning in August, our waiting room at the office was packed with the widows of men lost at sea, who wished to seek our advice regarding claiming pensions. Among them sat Harry's mother, long since estranged from him because he had refused to enter the Church. She was now bent on benefiting from his death by claiming a pension. I thought I would faint when she explained her business, and I quickly referred her to my colleague. Miss Evans. Then, deserting the waiting crowd, I fled to the unused cellars of the old house in which the office lay, and there in the clammy grime of adisused coal cellar, I stood shivering helplessly, so filled with shock that I hardly knew where I was. When, after a few minutes, my mind cleared a little, I was nauseated at a woman who could order her son out of their home because of a religious difference, and yet could coolly try to get a pension at his death.

I heard Miss Evans calling me and automatically I ran back up the stone steps. She met me on the upper staircase and scolded me for leaving clients waiting. Like a zombie, I moved to obey her orders. I did not cry.

I did not want to know this cold, grasping woman, Harry's mother, nor did I say anything to my own parents; there was no point in facing their probable derision at such a humble marriage. I could almost hear their cultured voices ripping apart a man I had loved dearly, and I could not bear that they should do it.

Somehow, I kept my mouth shut, but the unexpressed grief was like a corrosive at work inside me. It caused such damage that I never truly recovered from it. In a body made frail by much illness and, at times, near starvation, it worked its will.In a character already very introspective from childhood, filled with fear of grownups, its effect was devastating.

As a little child, I learned early that my parents were simply not interested in me, and that I had to face all the fears of childhood alone. As a young adult, I continued that early attitude of solitary suffering, and it was reinforced by the loss of the one person I trusted implicitly.

Though I did not consider it at the time, I had lots of fellow sufferers and, as a social worker employed by a charity working in the dock areas, I had to help to look after them. Our waiting room was daily filled by rows of weeping mothers and wives; every ship that went down seemed to have a Bootle man aboard. My mind is filled with memories of the overwhelmed resources of our little office, when the Athenia, the Courageous, the battleship Royal Oak, and hundreds of others, big and small, were lost in 1940 and 1941.

Sometimes the position was reversed, and a seaman's family was lost in an air raid.

My senior, Miss Evans, and I often faced a stony-eyed or openly weeping merchant seaman or a serviceman, sen

t home on compassionate leave because his home had been bombed and his family killed. Commanding officers did not always tell them why they were to go home. A few would go straight to their house, see the wreckage and realise what had happened. But quite a number reported directly to our office, as instructed by their Commanding Officer, and we would have to break the news to them. Because extended families frequently lived in adjoining streets, a man could find himself left with only a badly injured infant in hospital, and neither sister, aunt nor mother left alive to help him to care for the baby.

These heart-rending cases intensified my own sorrow to such a degree that I could not bear it any longer, and I decided I must try to obtain other work. Not only was I grief-stricken, I was also hungry. The salary that the charity was able to pay me was so small that I could not even afford lunch; I was poorer than most of the clients who thronged our waiting-room.

2

EVEN in 1940, there was much unemployment in Liverpool, and the competition for any job was still very keen. At first, when the war began, the number of unemployed was increased by firms going out of business as a result of the war. For example, my mother, so acid-tongued at home, used her superior-sounding Oxford accent to good effect as the representative of a greeting card firm. The company was suddenly faced with an acute paper shortage, and, in order to remain in business, they had to turn to printing products essential to the war effort; they did not need a sales force. Mother, by this time very experienced and quite nicely dressed, soon found a new job as an accountant in a bakery. Girls like me, however, were in direct competition with a large population bulge made up of babies born after the servicemen came home from World War I. We were now in our early twenties.Though by this time I was a skilled shorthand typist, as well as having had experience in social work, I was turned down again and again when I applied for secretarial posts.

The supercilious head clerks and typing pool supervisors looked me over as if I were a horse up for sale, often asked the most impertinent questions and always demanded references as to my moral character. They also asked about my education, and I had to own up that I had had only four years in school.

"Why?" they would snap suspiciously. "Were you ill?" and I would have to reply that my parents had kept me at home from the age of eleven, in order that I might keep house for my parents and my six younger brothers and sisters; it was essential to impress on them that I was extremely healthy, because no employer would consider a person who might miss days of work through ill-health.

They looked disdainfully at a sheaf of evening school certificates showing high marks, and then would often change the subject by making disparaging remarks about my poor appearance.I could not help the way I looked. My complexion was a pimpled white from insufficient food. My homecut hair hung lankly from lack of soap. In spite of working days and evenings, I could not earn enough to dress myself properly, even in second-hand clothes. When I could manage it, I bought little tins of Snowfire makeup from Woolworth's, at threepence a tin, to improve my looks, but often enough the expense was too great for my limited funds. I was neatly shabby to the point of beautifully stitched patches on patches, darns on darns.

Seventeen shillings and sixpence a week, which was what I earned, was only two shillings and sixpence more than I would have received on unemployment pay. Before I received my wages, deductions were made by my employer for National Health and Unemployment Insurance and for hospital care. The remainder was demanded of me by Mother. In those days, many mothers believed that they owned not only their daughters, but also everything their children earned, and my mother was no exception.

Money for my own expenses was earnedin the evenings, by teaching shorthand to pupils in their homes.

I always fell into a panic when I lost a pupil, because it often meant that I had no tram fares and must walk the five miles to work in Bootle, through quite dangerous slums. In winter, the walk had to be done in the dead dark of the wartime blackout.

Mother was not prepared to help me. She had at that time no intention of ever being a fuUtime housewife herself. Before Father went bankrupt, she had always been able to afford help with the children, had never had to care for them herself. She used every pressure she could think of to make it impossible for me to work, so that I would stay at home and be a free housekeeper. Even during the time that my younger brothers and sisters, Brian, Tony, Avril and Edward, were evacuated, she nagged and made my life a misery on this subject, presumably in order to have me ready at home to care for the children when the war ended. This remorseless battle between us had gone on for years, but I had always refused to give in.

I was quite sympathetic about Mother's preference to go to work, but I never couldsee why I should have to shoulder the burden of her responsibilities and become, once more, an unpaid, unrespected slavey to an uncaring bunch of siblings and two indifferent parents.

Perhaps Mother's lifetime repression of me had become a habit and closed her mind to the possibilities of other domestic arrangements. I knew from infancy that my very existence was a trial to her—she had always made that point extremely clear to me—and I tended to apologise continually to her as if I had no right to live.

Some time back, when, because of her callous attitude towards me, I had nearly suffered a nervous breakdown, she had become suddenly afraid; mental instability was much feared as a dreadful blot on a family's reputation. She promised she would treat me exactly as she did my pretty, compliant sister, Fiona, the third child of the family, now aged eighteen. Until I could command a better wage, she promised, she would take from me only about seven shillings a week, which would cover amply the food I ate.

She soon forgot her promise and fell intoa series of tremendous rages, until I again gave up all my wages.

Fiona, three years younger than me, earned the same amount as I did, but the money was, in practice, left with her for her expenses and clothing, as was often done in middle-class families. She always looked well dressed.

Alan, the brother next to me in age, was in the Air Force. Out of the miserable fourteen shillings a week which he was paid, he allotted seven shillings to my mother. I felt that this, also, was pressing too hard on someone who had very little. I was unwise enough to say so, and Mother blew up like a time bomb.

"It's the only way in which I can claim a government pension, if he is killed," she stormed.

As far as I was concerned, this remark put her into the same cold-hearted category as Harry's mother.

Before he was killed, Harry, my fiance, had been on several voyages to New York, and at different times had brought me three very nice dresses from the Manhattan garment district. Anxious not to give an indication that I was engaged, Ihad told Mother that I had bought them m a second-hand store. Together with a pair of satin sUppers, bought for my Confirmation and subsequently dyed black, the frocks enabled me to look appropriately dressed when I went to a local Dancing Club. Mother and Fiona often borrowed them. Since both of them were bigger than me, the seams were now showing signs of splitting.

Despite Mother's ruthlessness, from the spring of 1940 I had endured my lot more philosophically. I would be twenty-one in June and would marry Harry in the summer, when he hoped to have earned enough to furnish his house with the essentials, so that we could move into it.

Now I was alone again and so distressed that I believe that sometimes I was out of my mind. I would cry as I walked home through the darkness, and often cried through the night, while Fiona slept contentedly on the other side of the bed, and poor little Avril aged twelve, squirmed uncomfortably between us.

One very hungry day, I inquired at the Employment Exchange about joining the Wrens, the naval service. I saw myselftrim and smart in the navy blue uniform and tricorn hat of an officer.

The clerk told me sharply that, with my qualifications, I might get into the ATS, the women's service attached to the army; they needed kitchen help and drivers. I could not drive, and my present work demanded more skill than cooking for

the Army, so I turned down this suggestion.

Feeling crushed and lonely, that evening I spent an extravagant shilling and went to the dance club, where I had first met Harry; I craved warm, friendly people round me.

Norm, the owner, had a new record of In the Mood on his wind-up gramophone, and over the cheerful noise of it, he greeted me genially.

At first those dancers who had known Harry and me were a httle shy about asking me on to the floor. When they discovered that I was not going to weep for him on the padded shoulders of their best suits, I was never short of a partner. They were nearly all skilled workmen, for the moment exempt from military service; they were earning bigger wages than theyhad ever enjoyed before and had money to spend.

As a joke, I mimicked the pompous clerk in the Employment Exchange, who had so mortified me when I asked about joining the Wrens. A group of us were waiting for Norm to change the record, and the men gravely assured me that for a girl to join the Services was a fate worse than death.

With eyes averted, one man said, "It's not suited to a nice girl like you. You'd have a rotten time."

Another said with a grin, "Nice girls don't leave home; they stay close to their mams." He nodded towards his friends, and added, "When these lads get into uniform it brings out their tomcat instincts; regular tigers, they are." He exchanged playful punches with the others, and the conversation became ribald, so I left them. Truly, I thought, there is no one so conservative, small c, as a skilled craftsman. I trusted them enough, however, to feel that I should keep on trying for work as a civilian.

One of Harry's acquaintances escortedme home, and left me politely on my doorstep.

During that night, as I lay sleepless, I think I began to reaUse that I could not live my life alone, and that I hoped to meet someone a long time in the future, who would fill the frightful gap in my life. I was used to a large family round me. Homes were, indeed, more crowded in those days. Sometimes there was a grandparent or other relation living with a married couple with children, and a lodger or two; single men frequently rented a room and were boarded by their landlady, who sometimes became the target of malicious tongues. Elderly women, widowed or single, occasionally doubled up and also endured the disparaging remarks of their neighbours, in these cases, with regard to their sexual preferences. The concept of birth control was barely beginning to penetrate the densely populated area in which I lived; and in Bootle, a Roman Catholic district, it was almost unknown and, in consequence, families were huge.

The Lemon Tree

The Lemon Tree Thursday's Child

Thursday's Child Yes, Mama

Yes, Mama Madame Barbara

Madame Barbara Twopence to Cross the Mersey

Twopence to Cross the Mersey A Cuppa Tea and an Aspirin

A Cuppa Tea and an Aspirin The Moneylenders of Shahpur

The Moneylenders of Shahpur Lime Street at Two

Lime Street at Two Minerva's Stepchild

Minerva's Stepchild Three Women of Liverpool

Three Women of Liverpool The Liverpool Basque

The Liverpool Basque Liverpool Miss

Liverpool Miss The Latchkey Kid

The Latchkey Kid Liverpool Daisy

Liverpool Daisy Mourning Doves

Mourning Doves