- Home

- Helen Forrester

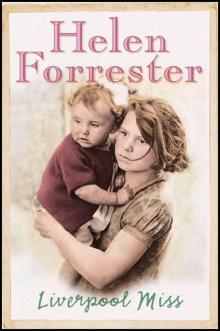

Liverpool Miss

Liverpool Miss Read online

HELEN FORRESTER

LIVERPOOL MISS

DEDICATION

To my family and friends who helped me to remember

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE

CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX

CHAPTER THIRTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER THIRTY-EIGHT

About the Author

Other Works

Copyright

About the Publisher

CHAPTER ONE

It had begun to rain and I was shivering, as I manoeuvered the squeaking Chariot over the road to the corner of Castle Street. Avril was red in the face with rage. She stormed at me because I would not take her out of the pram and let her walk amid the busy lunchtime crowd. At the other end of the pram, beneath the leaking hood, Baby Edward grizzled miserably for the same reason.

Since the October day was too cold for us to walk in the park, I had brought them into the city, thinking that it would be more sheltered and that we could amuse ourselves looking in the shop windows. And now we had wandered into the business district.

Pretty secretaries, rushing back from lunch, and smart businessmen, carrying umbrellas and brief cases, glanced impatiently at the intruding pram with two grubby urchins in noisy protest. It belonged away in the slums, like the tatterdemalion who pushed it.

I did not care. I was resigned to people staring at my long, wind-chapped, bare legs, at my toes sticking through a pair of old plimsolls, at an outgrown gym slip worn without a blouse, a ragged cardigan covering part of my nakedness.

Through the increasing rain, I pushed the pram dreamily amongst them. In my mind I was not walking in black, depressing Liverpool; I was in the countryside and then in the fine, old southern town from which I had been unceremoniously plucked two years before. It was market day, and Father and I were looking at the horses brought in for sale. As we moved about, the ploughmen, the shepherds and the farmers would touch their forelocks to the distinguished-looking gentleman, strolling around with a little daughter in the uniform of a good private school.

‘Echo! Liverpool Echo. Read all about it!’ shouted a man in a cloth cap, thrusting a paper towards the hurrying throng. I blinked, and hurriedly swerved to avoid him.

Would we always have to stay in Liverpool, I wondered depressedly. Would we always be cold and hungry?

‘Oh, shut up, Avril,’ I scolded crossly, and stopped the pram while I tucked an old overcoat round Baby Edward’s knees and then pushed the edges of it up over her lap. ‘Look, love. See up there – on the top of the town hall. There’s Minerva. She’s looking at you.’

Avril turned her woebegone face upwards towards the dome I had pointed out.

‘See,’ I said. ‘She’s smiling at you. Hasn’t she got a lovely golden face? But I think she’s got smuts on her nose, just like you.’ I touched Avril’s damp, little nose with a playful finger, and she sniffed and stopped crying.

Baby Edward could not see what I had pointed out; but, when I touched his nose and laughed at him, he saw hope of a game and tried to reach forward to touch my hooked nose. Tiny fingers grasped at my horn-rimmed glasses. I backed away hastily before they fell off.

Laughing at each other, we continued along the street.

Many people thought it was Britannia who sat looking down at Liverpool, but Father had told me it was Minerva, the Goddess of Wisdom, Invention and Handicrafts. He assured me that she also took care of dramatic poets and actors.

There were plenty of craftsmen in Liverpool of whom she might have been proud, even some actors and a poet or two, but most of them queued at the Labour Exchanges, their abilities unused. They stood idly round the dock gates, where ships lay in every stage of decay. They hung around outside the gaily lit public houses. Her sailors, skilled men, sat hungry in their cold kitchens, while their despairing wives nagged and their children went barefoot.

Amongst the defeated men in the queues at the Labour Exchange, Father had stood for over two years. Ruined by the Depression and, in part, by his own extravagances, he had brought us back to his native city in the hope of finding work. But, in the Liverpool wet, he had seemed like a lost butterfly, with wings beaten useless by the rain. He had watched, helpless, as Mother struggled, without medical aid, to recuperate from a major operation and a mental breakdown. Though the wartime marriage had not been a happy one, her degeneration into a haggard virago must have broken his heart.

To look at his seven children was almost too much for him. We were a hungry, ragged and increasingly unruly crew, disoriented by our parents’ disasters, seven small sparrows with our beaks open, loudly demanding to be fed.

Because Mother was at first so ill, I suddenly had thrust upon me, as the eldest child, the task of caring for her and for my brothers and sisters. The Public Assistance Committee gave Father forty-three shillings a week, out of which we paid twenty-seven shillings a week for three unheated attic rooms. The remaining sixteen shillings had to cover every need of nine people; and for a time it seemed certain that Baby Edward would die for lack of milk, and I often looked with terror at our empty food shelf.

Recently, a little hope had entered our lives. Father had obtained a small clerical job with the Liverpool Corporation. He earned only a few shillings more than the Public Assistance allowance and the extra money was swallowed up by his expenses. But it was a new beginning for him.

About the same time, we obtained a bug-ridden terrace house at a few shillings less rent than our rooms. I no longer had to face the irate complaints of the tenants in the rooms beneath us, about the noise the children made. The bugs bit unmercifully and they made a horrible smell, but the children did not complain.

I had high hopes, when Father started work, that I would be allowed to go to school and then to work, and that Mother would become the housekeeper. But Mother had obtained part-time employment as a demonstrator in various department stores, and she announced that she would be continuing this work.

‘Why can’t you stay at home, like other mothers do?’ I implored.

‘The doctor said I should work – remember?’

‘Yes. But that was when you were convalescent. He wanted you to walk about in the fresh air to get strong again. But you are quite well now.’

‘Oh, don’t be stupid, Helen. Stop arguing. We need the money.’

‘But must I always stay at home, Mummy? I’m over fourteen now. I should be at work – like other girls are. Couldn’t we find someone to help out at home?’

‘Really, Helen. Be sensible. How could we afford to pay anyone?’

We did need the money, it was true, and we never p

aid anybody we could avoid paying but I had all the adolescent’s doubts about my elders, and I distrusted Mother’s motives. There had never been much love between us. I had always been taken care of by servants; in fact, Mother had never had to take complete care of any of her children. I sensed angrily that she found it easier to go out to work than to stay at home and face the care of seven, noisy children. I found coping with six brothers and sisters, who daily became less disciplined, very hard indeed.

So, as I walked through the rain along Castle Street and absent-mindedly played with Baby Edward, and diverted Avril’s attention to Minerva and then to a warehouse cat stalking solemnly across the street, I was bitterly unhappy.

We had to stop, while a desk was carried across the pavement from a furniture van into an office building; and I looked again up at Minerva.

She seemed almost to float in the misty rain, and I wondered suddenly if something more than a statue was really there, some hidden power of ancient gods that we do not understand, and I said impulsively, ‘Hey, Minerva. Help me – please.’

The big man in a sacking apron, who was supervising the transfer of the desk, turned round and asked, not unkindly, ‘Wot yer say, luv?’

I blushed with embarrassment. I must be going mad with all the strain. I’m crazy.

‘Nothing,’ I said hastily. ‘I was just amusing the baby.’

‘Oh, aye,’ he replied, smiling down at Edward, while the desk disappeared through a fine oak doorway. ‘You can get by now, luv.’

CHAPTER TWO

I was not quite twelve when we came first came to Liverpool, and my parents were able to keep me at home because the Liverpool Education Committee did not know of my existence. I had come from another town and did not appear in any of their records. Six weeks before my fourteenth birthday my presence in Liverpool was reported by my sister, Fiona’s, school teacher. And much to my parents’ annoyance, I had to attend school for those six weeks.

Now I was over fourteen, my parents had no further legal obligations in respect of my education. So, at home I stayed, simmering with all the fury of a caged cat.

I had had an aunt, a spinster, kept at home all her life to be company to my grandmother, who lived on the other side of the River Mersey. This aunt seemed to have no real life of her own, and I dreaded being like her, at the beck and call of my relations, a useful unpaid servant, without the rights of a servant. She was such a shadow of a person that I never ever thought that she might help me.

I raged to myself that I was always the last to be provided with food and clothing. I did not even think about the lack of pocket money or other small pleasures – they were beyond my ken.

In our hard-pressed family, shoes and clothing were given first to those who had to look neat for work, and then to those who went to school. I could always manage because I did not have to go out, I was told sharply.

As housekeeper, I had to apportion the food. I fed Baby Edward first, then Avril, who was nearly five, then the two little boys, Brian and Tony. After them, frail, lovely Fiona and cheery Alan. I would then serve Father, who never complained about the small amount on his plate. What was left was shared between Mother and me. Sometimes there were no vegetables left for us, and frequently no meat, so we had a slice of bread each, with margarine, washed down with tea lacking both sugar and milk.

Mother still looked so dreadfully haggard that I would sometimes say, with a lump in my throat, that I was not hungry and would press the last remaining bits of meat and vegetable upon her. All my life I had been afraid of her tremendous temper, but such fear had long been overridden by a greater fear that she might die.

In response to my frequent complaints at not being allowed to go to work, Mother often said absently, ‘Later on, you will marry. Staying at home is good practice for it.’

But I had always been assured by Mother and the servants that Fiona had the necessary beauty to be married; and I – well, I did have brains.

‘You can’t help your looks,’ our nanny, Edith, used to say, as she scrubbed my face. ‘Maybe your yellow complexion is from being ill so much. It might improve as you get older.’ She used to seize a brush and scrape back my straight, mousy hair into a confining ribbon bow on the top of my head; but she spent ages curling Fiona’s soft waves into ringlets.

‘Why do you have to be so disobedient? You’re nothing but a little vixen, you are. Nobody’s going to marry a faggot like you when you grow up,’ she would shout exasperatedly. ‘Get those muddy shoes off, before I clout you.’

In a desperate effort to save myself from spinsterhood, I learned to obey a raised voice like a circus dog. But it did not do me much good. I was still sallow and plain, sickly and irritable.

After Father found a job, I fought a great battle with my parents for permission to attend night school three evenings a week. It became the single joy of my life. There was order and purpose in the musty, badly-lit classrooms with their double wooden desks in which, for most classes, sat more than forty pupils. The bare board floors, the faded green paint and chipped varnish were much more pleasant and clean than my home.

For the first two winters of my attendance, nobody would sit by me, because I was so blatantly dirty and I stank. Only the teachers spoke to me. In some subjects I was so behind that I needed dedicated helpers. And the teachers gave me that help.

The bookkeeping teacher taught me the simple arithmetic which I had forgotten through long absence from school. The English teachers gave me essays to write, in addition to the business letters they demanded from their other pupils. They drew my attention to poems and to essays I should read. Later, I took German and French, and again the teacher drummed additional grammar into me, and introduced me to the translated works of foreign authors. Shorthand, a possible gateway to employment, was largely a matter of practice, and I practised zealously.

I dreamed of becoming the treasured secretary of some great man of affairs, like Sir Montague Norman, the Governor of the Bank of England, to whom I had once been introduced. He had given the silent, small girl by Father’s side a new shilling, and I had curled up in an agony of shyness and refused to say thank you, much to Father’s embarrassment. But, of course, when I became a secretary, I would always be ready with the correct, polite remark and flawlessly typed letters ready to be signed.

During the day, as I walked little Edward in the squeaky Chariot and, particularly after my more trying charge, Avril, had joined her brothers and sister at school, I read books balanced on the pram’s raincover. I discovered Trevelyan’s histories and read all those that the library had. The librarian suggested histories of other countries, so I read, not only the histories of France and Germany, but those of China and Japan, of the United States and of the countries of South America.

The heroines of some of the Victorian novels I read studied philosophy in their spare time, so I plodded through the works of several German philosophers far too difficult for me.

‘Don’t know what they are talking about,’ I told Edward crossly.

I found a book by Sigmund Freud and decided that he did not understand females at all. And what was it that people were supposed to be repressing all the time? Men behaved like men and women behaved like women. How could they behave any other way other than by being natural?

I tied myself up in mental knots, considering Freud, and never associated his work with the strange spasms and longings in my own maturing body. To my mind, Freud did not seem to do so well at interpreting dreams as Joseph in the Bible did.

Beneath this rabid desire for an education, for knowledge, simmered a mixture of fear and rage: I felt my parents did not really care what happened to me, as long as I continued to serve them.

CHAPTER THREE

Despite our big family, I suffered great loneliness. When Father was not too tired he would sometimes talk to me about his wartime experiences in Russia or we would discuss eighteenth-century France, of which he had a considerable knowledge. Mother ordered; she did not

discuss. Without pen, ink, paper or stamps, I could not write to the school friends I had left behind in my earlier life. In fact, at first my parents refused obdurately to allow me to write.

‘Why not?’ I demanded crossly.

‘Because it costs money, and there may be some creditors who still want to trace your Father.’

They also forbade me to write to my grandmother, Father’s mother, with whom I had always spent several months of each year. Grandma, Father said, had been most unreasonable and he had quarrelled with her. I suspected that she had finally grown tired of the scandals of the gay life my parents had led before the Depression, and then of helping to pay their debts.

When I went to the local shops, I saw only older, married women, or children sent on messages, and, to me, some of the girls who lived in neighbouring streets seemed hardly human. On Saturdays and Sundays they went about in twos and threes, dressed in cheap finery. They gawked and giggled and shrieked at the gangling youths hanging uneasily about the street corners. Because their labour was very cheap, these girls had work in stores and factories. Once they were sixteen years old they usually joined their unemployed brothers.

Sometimes, when I passed a group of them as I pushed Edward along in the Chariot, they stared and laughed at me behind their hands. Garbed in the tattered remnants of my school uniform, occasionally with no knickers under the short skirt, I had to walk very uprightly lest a bare bottom be revealed to them. Once or twice they shouted at the idling boys to inquire which of them had ‘caught’ me. It was a long time before I realised that it was generally assumed that Edward was my illegitimate child. When I did discover it, I cried with mortification, because I knew that to have a baby out of wedlock was very wicked.

I was very vague about the origins of babies. I did not think about it very much. Dimly, uncertainly, I imagined that they came from the same place as foals and lambs and calves did. But I had never actually seen a birth and how this could be was beyond my imagining. I never equated men with stallions, rams or bulls. But, to be respectable, a child had to have a visible father or a substitute, like a gravestone, to account for his absence – that I knew. Once, when I was small, Mother dismissed our parlourmaid without a moment’s notice, and I knew from the maids’ gossip that she was expecting a baby – and she was not married.

The Lemon Tree

The Lemon Tree Thursday's Child

Thursday's Child Yes, Mama

Yes, Mama Madame Barbara

Madame Barbara Twopence to Cross the Mersey

Twopence to Cross the Mersey A Cuppa Tea and an Aspirin

A Cuppa Tea and an Aspirin The Moneylenders of Shahpur

The Moneylenders of Shahpur Lime Street at Two

Lime Street at Two Minerva's Stepchild

Minerva's Stepchild Three Women of Liverpool

Three Women of Liverpool The Liverpool Basque

The Liverpool Basque Liverpool Miss

Liverpool Miss The Latchkey Kid

The Latchkey Kid Liverpool Daisy

Liverpool Daisy Mourning Doves

Mourning Doves